DotSight Scanner – new tool for the visually impaired

Discover DotSight Scanner, an innovative tool for the visually impaired, through the insights of Ján Bujnovský. This app digitizes braille texts, making them accessible and preserving important documents. Ján will share the project's goals, design principles and challenges, as well as plans for the future. Don't miss our previous interview with Ján, in which we discussed his inspiring career transition from the chemical industry to IT.

Can you tell me more about the project you are currently working on – a scanner for the visually impaired?

The main purpose of the DotSight Scanner is the digitalization of braille texts that are currently only in paper form. There are many books and documents in braille that are only available in physical libraries, so this app is a tool that will make those texts more widely available to the whole community.

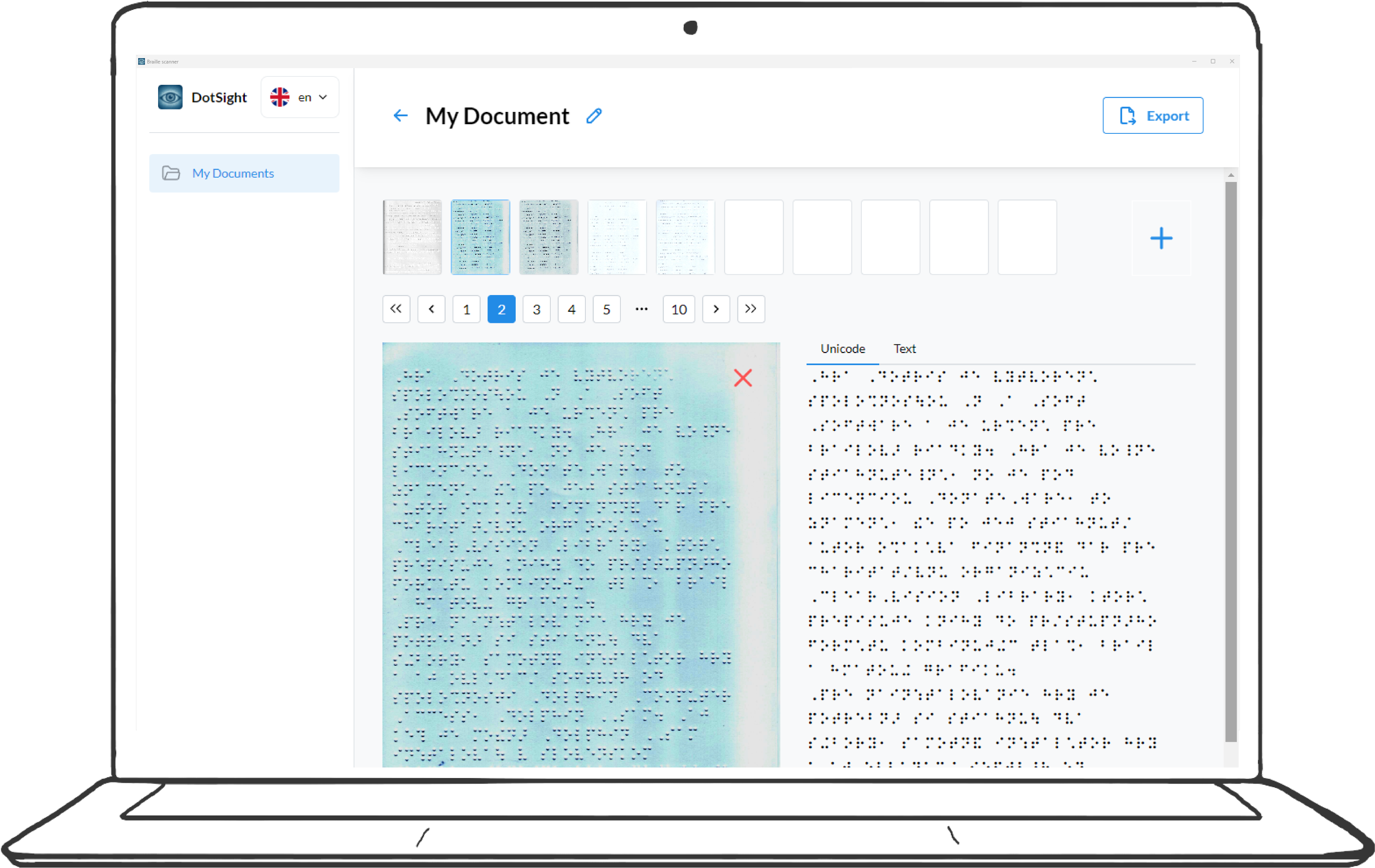

It's actually a desktop application that will work in two ways: connecting to a physical scanner (e.g. a printer/scanner, but not a phone-scanning app as it is often difficult for the visually impaired to take pictures with a phone) or reading from images that have already been scanned.

The app can recognize braille text (the dots that blind people read using their sense of touch) and convert it into digital form – both as braille dots (known as unicode – the worldwide standard format of braille text) and as standard text. The user can then read the texts either as braille dots using a tactile machine reader, or using screen-reading software that reads out the standard text.

What were the main design principles you needed to consider when developing the scanner?

It was very important that every part of the HTML code (such as buttons or headings) was properly tagged with a description. This was to ensure that the screen readers (which blind people use to listen to texts) would be able to read that description and ensure the final output is understandable to the end user.

Is feedback from visually impaired users included in the development process?

Right now we're testing the app with members of the Slovak Braille Authority and Union of the Blind and Partially Sighted, who are giving us feedback. Once the app functionalities are fine-tuned, we plan to make it available for the whole community of the blind and visually impaired.

Did you encounter any technical challenges while developing the scanner, and how did you overcome them?

The biggest challenge was regarding the recognition of braille documents that have braille text on both sides. In these cases, the recognition model has to distinguish between the raised braille dots on the one side, and depressed braille dots showing through from the other side of the paper. We resolved this by decreasing brightness and increasing contrast in the scanning settings. This was quite interesting. When you scan standard text, the ink of the text is what you need to see and the more light you have, the easier it is to distinguish the letters. But when you scan braille text, it is the shape of the paper that makes the text, and the true shapes of the raised vs depressed braille dots are more visible with less light.

Did you work with any organizations or professionals in the field of visual impairment during the development of the scanner?

Yes, we’ve been working with the main coordinator of the Slovak Braille Authority, who is also the vice-president of the Slovak Union of the Blind and Partially Sighted in Košice. He is our main contact, and has been helping us test the scanner.

We previously worked together on the Braillee project, which led us to work together again on this scanner project.

Are there any specific design features or functions aimed at making the scanner user-friendly for people with varying degrees of visual impairment?

Yes, it’s designed for both partially sighted and blind people to use, as the text is converted to braille as well as standard language for use with screen readers.

For the partially sighted users, the main guideline was to be careful about contrasting colors, which can make reading much harder. So we have kept to a fairly simple design. This is all still to be fine-tuned, as we’re still mostly dealing with the basic functionality at the moment.

What do you see the impact of this scanner project being on the visually impaired community?

We think it could have a significant impact, not just making more texts accessible to more people, but also in saving archives of old braille books or documents that don’t have any digital forms, and in helping larger institutions and libraries to transcribe books that previously or otherwise would have to be done manually.

There are also various different notations it could help with, such as digitizing braille sheet music.

Are there any plans for future improvements or updates to the scanner's features based on ongoing feedback and technological advances?

So far the future plans are unclear, as testing is still ongoing. But it’s possible we’ll link it to Braillee (our previous project) and language libraries so that it's not only available for use in English and Slovak languages (as is the case right now). We might also add some UI/UX changes to the scanner so that, for example, text can be edited. As recognition is not always 100% accurate, we also plan to integrate some form of spell checker in the next phase, possibly also using LLM (large language model such as GPT4) for final text editing.

What does one need to use the app?

Currently, Windows is required to use the app, although we are working on a Mac version as well. Connecting to a physical scanner is optional, as the app can also recognize braille unicode from previously scanned images or documents. However, it’s recommended to re-scan documents using the app whenever possible, as the app settings are adapted to ensure the best scanning results for the recognition software, which in turn means the best end results.

What similarities do you see between the scanner and the Braillee project?

Both applications help people with visual impairments, but they are quite different in their usage. Braillee is more technical; it’s about translating braille into language (and vice versa) and adding translation tables that make it easier for the blind and visually impaired to improve their writing and communication methods. DotSight, on the other hand, is for digitizing braille documents so as to preserve existing texts and make them more accessible, so it is designed for the more "mainstream" user.

READ MORE

DotSight Scanner – new tool for the visually impaired

A tool for digitizing braille texts and enhancing accessibility for the visually impaired. Learn how this innovative application is transforming access to braille documents.